From the first time I saw it, December 5 of last year, I felt compelled to go long about Hayao Miyazaki’s The Boy and the Heron. I felt, and still feel, that it is probably the best film of the 21st century. We’re talking here about a film I saw five times in cinemas; in what was a very trying 2023 holiday season, it was a balm. By the time 2024 rolled around the three iterations of the track “Ask Me Why” (“Evacuation,” “Mother’s Message,” and “Mahito’s Commitment”) had already gained Pavlovian control of emotions: all it takes is the first notes to set me at ease and/or put on the edge of tears.

And it’s for that exact reason that I’ve waited over a year to write this piece. Punting it down the road, then punting it again, afraid that I was clinging to it not out of love, but out of necessity. Sure, I love every Miyazaki film, but what if this one is different? I saw the growing case for its good-not-greatness online (a script that’s too sloppy, themes that never coalesce) and felt compelled to wait until I had a chance to see it again at home. A one year anniversary piece, I told myself, that’s what it will be if I still love it. Well, you’ve seen the title.

For about two months now I’ve been meditating on what exactly it is I want to say. I wanted to write about how The Boy and the Heron can be read as an extension of the film that came before it, The Wind Rises, and how it is kind of answering the questions its predecessor poses. I wanted to write about how The Boy and the Heron evolves Miyazaki’s pet theme—What’s the point of doing anything when the world is ending?—particularly as it relates to the imminent anthropocene. I wanted to write about the ending: it matters that Miyazaki a man old enough to remember the second world war, sees history repeating otseld and, despite it all, still makes films for and about children, films that say, ‘Shit’s fucked, and you shouldn’t have all this responsibility, but have hope, I promise you’ll figure it out. I promise you can do better.’

And then—just at the moment when I was finally ready to put “pen” to “paper,” to hit all-systems-go on that piece—my grandfather died.

The protagonist of The Boy and the Heron is Mahito Maki. He is ten when we first meet him. It is the middle of the night; he is awoken by air-sirens. Household servants scrambling by, we catch fragments of conversations: Where is his father? Does he know? The allies have bombed the hospital where his wife volunteers. It’s burning.

Mahito whips into action. His father intercepts him, orders him to stay home. He disobeys. At the door he puts on the wrong shoes, Geta, and has to circle back to change into something more practical. It’s a moment of Miyazaki humanism—comparable to Satsuki and Mei getting so overexcited about exploring their new home in My Neighbor Totoro that they, running, giggling, barrel straight past the door that they intend to enter, out of frame… and then back into frame when they realise their mistake; action that exists not because it accomplishes something narratively, but because it it human, and it feels right for it to be there—but any charm there is to be found in this incidental, mundane moment evaporates as Mahito approaches the hospital. The air thickens with ash and smoke and embers. He struggles through the crowd who are trying to get the blaze under control so that might get someone, anyone out. The animation blurs and swirls, like watercolour without any water. He arrives to find the hospital an inferno, already a charred skeleton of a building, on the brink of collapse.

As viewers we know that there was nothing he could’ve done, his mother is already gone. But it’s not hard to imagine that in his mind that split-second delay with the shoes is the difference between saving her and losing her, the reason he never got to ask a thousand questions, the reason he never got to say goodbye.

I don’t remember the last thing I said to my grandfather. We spoke briefly on the phone a few times throughout the year. We spoke about his health (which wasn’t great) and my work (which is fine, lol). I am not the most emotionally expressive person, and neither was he, and since becoming an adult we often interacted like that average man conversation meme. When we said goodbye to each other in person, we shook hands rather than hugging; when we said goodbye on the phone, I normally forwent the ‘I love you,’ which I sensed made him feel a little uncomfortable, and opted for something a bit more formal. I don’t worry about what I said to him the last time we spoke because there was one final thing that I needed to tell him, that wasn’t the way our relationship worked. He knew, of course he did.

Every time I watch The Boy and the Heron I am caught off-guard when the voiceover begins. It’s a technique that Miyazaki normally avoids. His characters have rich interior lives, but we’re not really privy to them. My reading has always been that he prefers to let action be the loudest element of a character. It doesn’t matter what you think; it only matters what you do. The most virtuous thoughts, the most well-staked ethics, these are less valuable than the person who second-guesses everything they do, goes on long-complicated journeys of selfishness and smallness, but who ultimately acts.

On my first viewing, familiar, as I am, with Miyazaki’s biography, and already noting parallels in the narrative, the appearance of voiceover had me worried that the film was going to be a typical late-career piece. Endearing but flawed, too enamoured with nostalgia to muster the bite of his greatest works. I should’ve had faith. Rather than inviting us in, Miyazaki uses the voiceover to push us further out. Mahito only has two voiceover lines. (‘Three years into the war, mother died. And a year later, my father and I left Tokyo.’ And, ‘Two years after the war, we returned to Tokyo.’) They are positioned as bookends, but do not provide narrative unity or sense of closure. They feel like sentences pulled from the middle of a large paragraph, like a much older Mahito is explaining his childhood to someone and is brushing over this episode in his life. There was a Mahito before the film, and a Mahito who continues on afterwards, and all we are seeing is a short window of continuity.

Every character we meet is painted initially in broad brushstrokes This is Mahito’s father: he is stereotyped as the absent, overworking, domineering type. This is his father’s new wife—Mahito’s aunty-cum-step-mother—who courted, married, and conceived a child in the year following his old wife’s death: she is stereotyped as the formal, well-meaning. but emotionally insensitive type. There are the old-lady house-servents who possess individual traits, like the chain-smoking, grouch Kiriko, but ultimately function more as an entity than a group of individuals: they are stereotyped after the seven-dwarves, a hint at the fantastical direction the film ultimately moves in. There’s Mahito’s mother who, like so many mothers in children’s fiction, is dead before the narrative begins. And then there’s Mahito, stoic and industrious, well-behaved and obedient: the little adult stereotype to a T.

The magic trick of The Boy and the Heron is how is peels back these stereotypes. Like the Mahito’s voiceover, we are not getting whole pictures of these people, but glimpses only, and these people are complex beings with rich histories that extend far beyond their ability to articulate, let alone the film’s capacity to fully capture.

Consider Kiriko, who we meet as an elderly house-servant, but subsequently learn worked as a fisher woman in a fantastical Wonderland-like domain that exists underneath and out-of-time with our reality. We only learn this because Mahito goes to this domain himself, and stumbles upon this young Kiriko entirely by chance, and even then he is only there for a few days. We are left to speculate: how many other lives has Kiriko lived?

But nowhere is this idea better deployed than at end of the film’s first act when Mahito discovers a book left in his room, a copy of Genzaburo Yoshino’s How Do You Live, with an inscription in the front. The hand-writing is his mother’s: ‘To grown up Mahito.’ He reads it—and begins to cry. We don’t know what part of the novel has set him off; we don’t know what his mother’s intent was, leaving this book for him; these people possess interior lives that we are never privy to, that they are barely privy to, everything is visible when you take the time to look, but no matter what you do it’s forever out of reach.

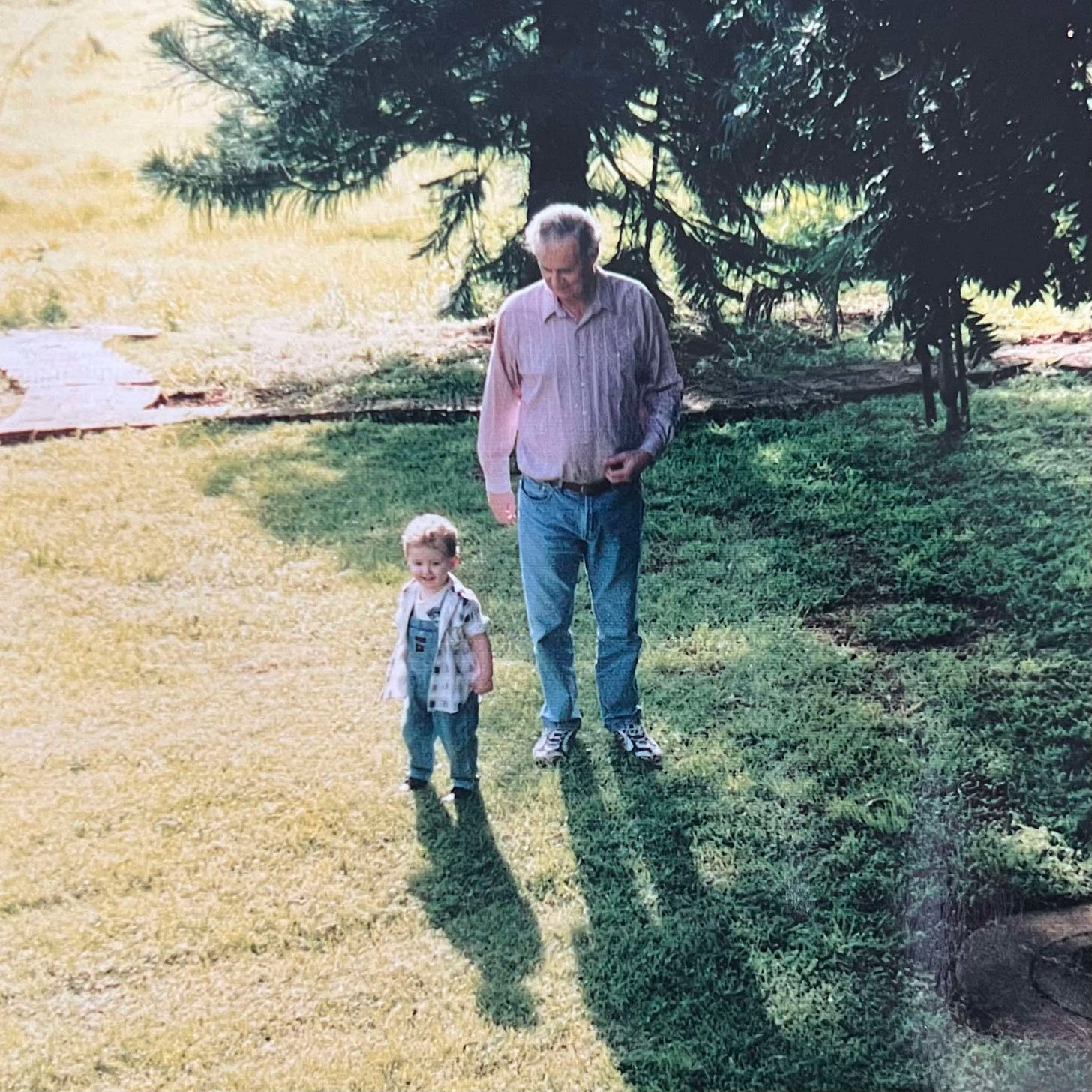

It’s impossible to take stock of someone’s life without list-making. Events, personality, relationships: they are like items on a receipt. This is something that I felt acutely at my grandfather’s funeral. Various people—his brother, my uncle, my mother, my sister—spoke about him, the kind of person he was: patient, practical, someone who let his actions speak. But I could not help feeling that—like Mahito summarising a world-jumping, fantasy adventure as the time he lived away from Tokyo—these eulogies, in their attempt to catalogue everything, were eliding a great amount of detail too.

Perhaps I only felt this way because I realised just how much of my grandfather was unknown. His brother told an anecdote of him as a young boy, creating an intricate system for scoring cricket. It was a charming story, perfectly congruent with who he would become later in life—the man who refereed for his local bridge club, who enjoyed complex World-War Two board games—and yet no one else had ever heard it before. I certainly hadn’t. And neither, to my great surprise, had my mother. Here was a facet of her father, someone she had known her entire life, revealed only now.

My mother and grandmother have remarked, from time to time, that some of my behaviours remind them of him. Like him, I have a fairly practical outlook on things: I, like him, prefer to solve a problem then complain about them. I inherited his love of cataloging, of complex strategy: I list-make about movies, about box-office and awards season, the same way he did about cricket. And I operate on the same emotional register that he did: big expressions of emotion do not come naturally to me, nor did they to him, and it’s something I am working on doing more. That’s why, although we got on well, we often said very little to one another; that’s why I normally forewent the ‘I love you’ at the end of a phone call.

At the funeral, hearing anecdotes, seeing photos taken throughout his life, I realise how much I didn’t know. So many of our interactions were silent: that time when I was eight and we played chess, and he didn’t go easy just because I was a child; that time—this was back when my family went to church—that time I asked him why he didn’t believe in God, and he explained his atheism, and his views on organised religion. These were teaching moments, and in that way I knew him well, because I understood his worldview, his values—and a great many of them have become my worldview and values. But these are only a portion of a person, and because our relationship was defined so often by silence, because our communication lay more in action, there remains so many things that I never learnt, things that I wished I asked.

I stated earlier that The Boy and the Heron is not a typical late-career film, that it is not pudgy with nostalgia—but that is not entirely true. Miyazaki does allow himself one indulgence. In Starting Point, 1979-1996, Miyazaki mentions that one of his greatest regrets in life was not asking his parents more questions when they were alive, not having serious conversations that he ought to have. He affords Mahito the opportunity he was denied, a chance to talk again to his mother—albeit not the way that you expect.

In the back half of the film, Mahito travels to the underworld. It is a world that is mostly ocean, mostly abandoned. There are spirits, Warawara, who ascend into the sky to become people. There is Kiriko, who captures fish to feed the Waraware. There are birds; they feed upon the Warawara, because the world is dying and there is nothing else for them to eat. And then there is a girl, a sorceress. She is the same age as Mahito. Her name is Lady Himi. She uses flame magic to defend the Warawara. She also happens to be Mahito’s mother.

Now, I’m not interested in explaining why Mahito entered the underworld, or how a young version of his mother (and Kiriko) came to be there, or how they exist simultaneously. If you have seen the movie then you know; if you haven’t, and you want to, then go watch the movie, silly. What I am interested in is a brief exchange, right at the end of the film. At this point the underworld’s decline has progressed from slow to sharp: everyone must exit, return to the real world, to their own times. And, despite knowing that his mother has to go back to her time, to meet his father, to give birth to Mahito, he can’t help but beg her not to go, to return with him to his time instead.

‘My door is a different one,’ she says. ‘I have to go there to become your mother.’

‘But if you go back there you’re going to die,’ Mahito says. ‘In the fire at the hospital.’

‘Fire doesn’t scare me. You know I’m really lucky to have you as a son.’

‘Please don’t. You’ve got to live, Himi.’

‘I hope you know what a good boy you are.’

I remember the first time I watched The Boy and the Heron, during this moment, knowing suddenly—fully—that this was going to be one of my favourite films. It’s the premise of Back to the Future, the twist from arrival, the emotional core of every good Doctor Who episode, all rolled into one. It’s the kind of concept that cuts through the things we say to ourselves—Miyazaki’s claims that he wishes he’d had more tough conversations with his parents; me saying my grief stems from all the aspects of my grandfather I’d never found out—and it homes in on the truth underneath those statements, that knowledge is not understanding, that you can be across a biography without any kind of connection, or never say a word to someone and yet share an invisible corridor with them—the kind of corridor where you know that ‘Three years into the war, mother died. And a year later, my father and I left Tokyo… Two years after the war, we returned to Tokyo’ is not bland description, but a statement with charge and implication—and that for all the things we wished we’d said, wished we’d learnt, for all the inscriptions in books that we want deciphered, for all the childhood stories about cricket scoring that we wish we’d heard, we’re really just taking a roundabout way to say one thing, the same thing, the obvious thing, the thing that doesn’t need saying but is still worth saying, worth saying a hundreds times over, and then once more: I love you.

Omg, that is amazing and I love it. A beautiful tribute to your incredible grandfather wrapped in a review of one of your favourite movies. I love you boyo.

And yet it was also a couple of thousand words that tell a different story altogether. Some of your best writing. For someone who claims to not be very emotionally expressive, you don't pull these punches.